The Body Remembers: Dance, Faith, and the Ghosts of Poe

Dance, like any language, draws its power from what it dares to say. Too often, I see work that whispers and never speaks. Choreography that floats and dazzles but refuses to carry weight. As if the body exists untouched by war, faith, lineage, or trauma. I do not blame the dancers. I blame a culture that rewards aesthetics over truth and abstraction over conviction.

When I enter the studio, I do not aim to entertain. I aim to bear witness. To what we lost. To what we never named. To the way a body breaks, not from weakness, but from memory. When ballet tells the truth, it becomes a kind of prayer. Not a closing of the eyes, but an opening. Not an escape, but a reckoning.

Edgar Allan Poe arrives already burdened by caricature: the drunk, the goth, the mad genius. Look closer and another story emerges, one that mirrors our own moment with unsettling clarity. Poe lived through the slow disaster of tuberculosis and watched it claim nearly every woman he loved. He carried the ache of anticipatory grief. He moved through a nation fractured by slavery, class division, and moral blindness. His sorrow did not romanticize itself. It devastated him spiritually.

As Dr. Harry Lee Poe explained to me, Rufus Griswold, Poe’s literary executor, distorted the story and painted Poe as a drug-addled lunatic. That portrait stuck. The real Poe looked nothing like it. He worked as a critic and humorist. He loved music. He thought deeply about faith. He mourned in public before grief had respectable language. He wrestled with belief in ways that still resonate. His final words, “Lord, help my poor soul,” ask for fuller hearing.

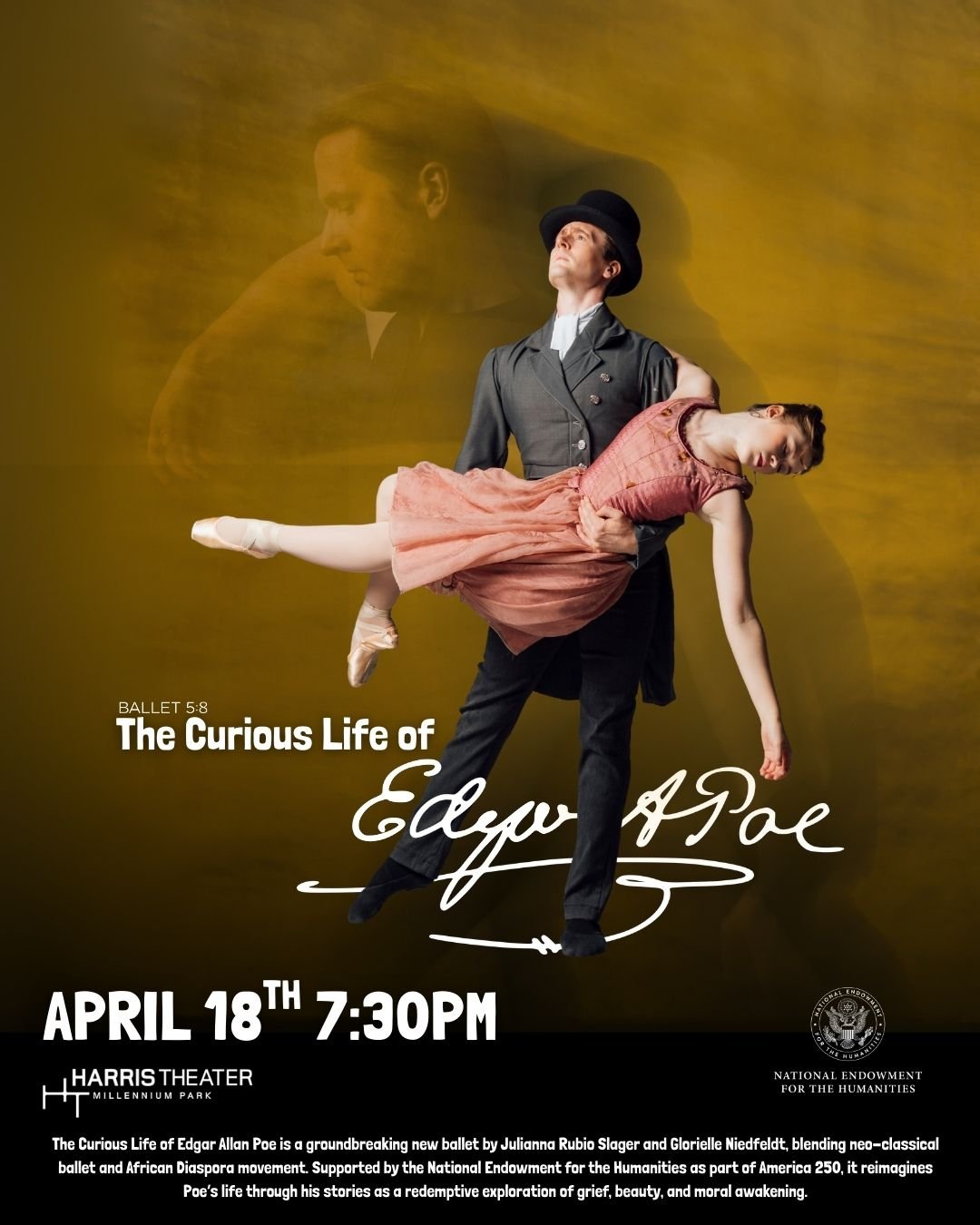

This ballet, The Curious Life of Edgar Allan Poe, does not function as biography. It acts as an exorcism. It dismantles myth. It reaches, I hope, toward resurrection.

The World Premiere of Edgar Allan poe is April 18th at 7:30PM. The Lobby opens at 6:30PM with an exhibit on Poe’s Life and Contra Dance.

Grief resists the stage. It does not clean itself up or arrange itself into counts of eight. It does not behave. But it moves, often without permission, and it stays in the body long after language collapses.

While choreographing Poe’s early years, I kept returning to the loss of his mother, Eliza. Tuberculosis took her when he was two. His father had already disappeared. The Allans, a wealthy Richmond family who owned enslaved people, took him in. I imagine her absence as an open wound that never clots. In the studio, we shaped a physical vocabulary around that emptiness. Reaching gestures that never land. Spirals that cave inward. The servants and enslaved workers carry the rhythm of labor, slow and unbroken, ignored by design. They move constantly and remain unseen. They form both literal and spiritual ground.

Poe carried layered grief: personal, historical, cosmic. That complexity pulled me toward Eureka, his final and most misunderstood work. Neither poem nor essay, it moves as theology disguised as astronomy. Poe writes, “In the original Unity of the First Thing lies the cause of all things.” He names divine design. Sacred pattern. Beauty born from collapse.

That sentence anchors the ballet. We project it. We orbit it. We unravel it. Grief also has shape, and sometimes that shape leads home.

Ballet values clarity, symmetry, restraint. I honor that tradition until it stops telling the truth. When the story demands rupture, I break the form. I do not rebel for effect. I return to the spiritual core of dance.

Poe believed poetry should unfold in one sitting, powered by intensity rather than length. I think about choreography the same way. What stays in the body? What strikes like a chord and refuses resolution? I do not want dancers who pose. I want dancers who testify.

In The Tell-Tale Heart, the heart does not dance. It sounds. It presses. It haunts. We used rope pulled from Poe’s own writing quill. Creation turns into entanglement. His words ensnare him. Projections of his script flood the stage, crawl up the walls, and climb his body until only one word remains: GUILT.

That arc mirrors spiritual conviction. We begin with voice and creation. We end, if we wait too long, in confession.

Grace still remains possible.

Poe’s story refuses separation from America’s story. He grew up in the antebellum South, educated among wealth and violence, shaped by a culture that prized decorum over justice. He never publicly condemned slavery. Yet, as Dr. Poe reminded me, he felt deep sympathy for the poor and contempt for aristocratic excess.

How do we hold that contradiction? How do we choreograph brilliance alongside blindness?

I placed the servants and enslaved workers at the center of the ensemble. They do not fade. They press inward. They shape the world. In The Masque of the Red Death, they arrive not as background but as storm. Their rhythm fractures the waltz. Their presence echoes Poe’s inner reckoning.

They do not teach a lesson. They carry spirit. They stand as the unacknowledged saints of American history, the ghosts we refuse to name. In a nation still addicted to whitewashed narratives, placing their movement at the center felt sacred.

That tension reaches its peak in The Raven. The Raven does not read as bird but as voice. Memory. The presence of those crushed beneath history. The dancer is Black. Her movement cuts and claims space. She does not ask. She takes. Poe collapses not from weakness but from listening at last.

By the end of his life, everything unraveled. Virginia, his wife and muse, died after years of illness. He stopped writing. He wandered. Then something shifted. Dr. Poe points to signs of spiritual conversion. Poe spoke of heaven. He attended a Sons of Temperance meeting. His final days suggest surrender.

The final scene, Altar Call, begins in stillness. Poe stands shirtless, stripped of reputation and defense, kneeling at the front of the stage. The women of his life, Eliza, Frances, Virginia, Ligeia, circle him. They do not rescue him. They witness him. The ensemble gathers. The rope disappears. The projections fall away. Light remains.

We let the moment breathe. No choreography. Just a body cracked open.

Something sacred happens there. Not resolution. Release.

Faith, at its truest, does not flinch. It looks at the wound and stays. It listens. It makes room for contradiction. Good choreography does the same. It does not tidy loose ends. It exposes them.

When I make work, I do not preach. I remember. I trust the body to hold memory beyond language. I trust the stage to become an altar if we allow it. A place for mourning, recognition, and grace.

Poe’s story does not offer triumph. It offers ache, awakening, and ambiguity. In that ambiguity, I found faith. Not the kind that simplifies, but the kind that expands. The kind that listens to a heartbeat beneath the floorboards and asks what we still refuse to hear.

In the end, The Curious Life of Edgar Allan Poe speaks beyond one man. It speaks to all of us. Our grief. Our silences. Our hunger for light. And the God who still meets us in the dark.